Émile Durkheim (1858-1917) - Fellowship

With Émile Durkheim (1858-1917), the Unit takes up a founding figure of the social sciences who was received with the greatest respect worldwide. Marcel Mauss, Marc Bloch, Maurice Halbwachs, Pierre Bourdieu and Bruno Latour, Mary Douglas, Talcott Parsons and Jeffrey C. Alexander all refer to Durkheim and his journal, the Année sociologique. In view of Durkheim's belated reception in Germany, it makes sense to honour the author by establishing a corresponding fellowship, who was influenced by his studies in Germany in the 1880s, including Wilhelm Wundt. The anti-Semitic ostracism of Émile Durkheim during National Socialism, who said of himself ‘avant tout je suis fils de rabbin’, left its mark in Germany, which could be countered by naming a research centre after Durkheim for the first time.

The Research Unit aims to address the challenges of the 21st century, which manifest themselves in various crises that were first analysed by Durkheim in their breadth and interconnectedness. We encounter these crisis-like developments as the consequences of climate change, the return of war, the dramatic crisis of democracy, the inequality in the distribution f wealth and prosperity on a global scale or the crises of the ‘mind’ in times of extensive digitalisation and the advancement of artificial intelligence.

The concept of crisis, whose origins Reinhard Koselleck locates in Rousseau, and which Durkheim reserves for the so-called ‘anomic’, i.e. insufficiently regulated, division of labour in his study on the division of labour (‘De la division du travail social’), is inscribed with an appealing character. As soon as a phenomenon is recognised as a crisis and defined as such in public, there is a call to action! What about the perception and definition of what is considered a ‘crisis’, i.e. the ‘découpage de l'objet’ as Durkheim calls it?

Are there commonalities in the dynamics of crisis development and the structural upheavals associated with it?

With Durkheim's ‘toolbox’, which still contains the unsettling thesis of the ‘normality of crime', perhaps also of the 'crisis', it will be possible to approach these questions in a methodological and systematic way without falling into a 'Durkheimology'.

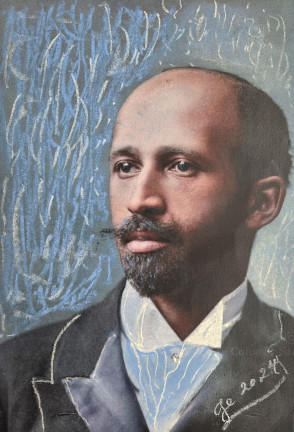

W.E.B. du Bois (1868-1963) - Fellowship

The naming of a professorial chair for People of Colour within the Émile Durkheim Research Unit at the University of Bonn would honor an unparalleled intellectual legacy deeply rooted in the critical sociological analysis of race, coloniality, and structural inequality. The works of W. E. B. Du Bois, including The Souls of Black Folk (1903) and Black Reconstruction in America (1935), remain foundational for understanding the historical and contemporary experiences of Black people as well as other racialized groups positioned within colonial, postcolonial, and capitalist power relations. Central to this legacy are Du Bois’s analyses of “double consciousness” and the entanglement of race and class within globally operative regimes of domination. These contributions can be convincingly aligned with Durkheim’s focus on social facts and the structural forces that produce, stabilize, and naturalize social hierarchies.

Du Bois’s significance for classical sociology is further evident in his transatlantic intellectual entanglements with European social theory. He met Max Weber during Weber’s journey to the United States in 1904, and it is plausible that Weber’s constructivist understanding of “race”—conceived as a socially produced “belief in commonality”—was also shaped by Du Bois’s early analyses of racialization, social inequality, and epistemic marginalization, as emphasized by Lawrence Scaff. This connection, however, reaches further back: during his period of study in Berlin (1892–1894), Du Bois attended lectures by Weber and engaged intensively with the German historical school, particularly the work of Gustav Schmoller and Adolf Wagner. These intellectual traditions were likewise formative for Émile Durkheim’s own encounter with German scholarship, rendering Du Bois a central—though long marginalized—mediating figure between transatlantic sociological traditions.

The concept of double consciousness developed by Du Bois in The Souls of Black Folk continues to offer a powerful analytical framework for examining the psychological, cultural, and social tensions experienced by People of Colour in societies shaped by colonialism, enslavement, and racism. Identity is thus understood not as an essential attribute, but as a historically produced outcome of violent power relations and enduring structural exclusions. This perspective is particularly relevant for analyzing the effects of colonialism, imperialism, and globalization on the lived realities of People of Colour, and it positions Du Bois as a central reference point for postcolonial social theory.

Du Bois’s work on race and capitalism, particularly Black Reconstruction in America, compellingly demonstrates how capitalist modes of production, colonial exploitation, and racialized systems of order have been historically intertwined. In doing so, Du Bois challenges reductionist interpretations of social inequality and makes visible how the systematic marginalization of Black people and other People of Colour has been constitutive of modern societies and continues to be so. These insights are central to understanding contemporary global inequalities, without resorting to cultural essentialism or individualizing explanations.

While thinkers such as Léopold Sédar Senghor made significant contributions to Black and postcolonial intellectual traditions—most notably through the Négritude movement—Du Bois is distinguished by a broader, explicitly sociological and intersectorally resonant approach. His empirical studies, such as "The Philadelphia Negro" (1899), alongside his autobiographical-theoretical reflections in "Dusk of Dawn" (1940), combine methodological rigor with a consistently power-critical perspective on racialization, knowledge production, and social order.

Against this background, Du Bois’s empirical precision, theoretical innovation, and sustained focus on Black people and People of Colour within global power relations render him a particularly compelling namesake for a Durkheim Research Unit devoted to the analysis of complex social structures, historical inequalities, and postcolonial social formations.

Mary Douglas (1921-2007) - Fellowship

Anyone who has ever met the grand old lady can hardly escape her influence.

It is her groundbreaking work that has earned her extraordinary recognition throughout the world and not only among ethnologists: 1963 The Lele of the Kasai; Oxford University Press, London. 1966 Purity and Danger. An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Tabo; Routledge & Kegan Paul, London 1970 Natural Symbols. Explorations in Cosmology; 1973: revised edition; Barrie & Rockliff/Cresset Press, London 1978 The World of Goods. Towards an Anthropology of Consumption; with Baron Isherwood; Basic Books, New York 1980 Evans-Prichar; Fontana Modern Master, Glasgow 1982 Risk and Culture: An Essay on the Selection of Technological and Environmental Danger; with Aaron Wildavsk; University of California Press, London 1986 How Institutions Think; Syracuse University Press, New York 1993 In the Wilderness: Doctrine of Defilement in the Book of Number; Sheffield Academic Press, Sheffield. She worked in the spirit of Evans-Pritchard, but also in the name of Émile Durkheim, whom she admired. I can personally confirm this, because I honored her with what I considered to be one of my best Durkheim portraits on the occasion of a visit to Bonn University and, as her husband assured me, she seems to have held it in special honor... Geographically, it covers the ethnic groups she studies in Africa and elsewhere, and the scope of her topics is of particular interest to the Émile Durkheim Research Unit: the use of rituals for the understanding of the human condition, the role of symbolic representations and the inherent power of symbols, as well as the relationship to “nature” as it is developed and practiced in religions... „Risk“ and „danger“ are basic concepts of a theory of crisis, in the development of which her creative spirit will be fruitful.

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (Bhīmrāo Rāmjī Āmbēḍkar 1891 – 1956) - Fellowship

Anyone who has ever been to India will have noticed the numerous Ambedkar statues as an expression of reverence for the scientist who made such an important contribution to the genesis of the Indian constitution. As a member of the Mahar, a population group traditionally counted among the Dalits, Ambedkar fought against social discrimination through the system of categorisation in Hindu society, which left its mark on India's eternal constitution, whose precious scrolls are preserved in helium. In 1922, Ambedkar was enrolled at the University of Bonn as the son of a general, even though his father was probably only a simple officer. But this position was a prerequisite for him to grow out of the group of ‘untouchables’. His last academic contribution, on ‘Marx and Buddha’, was the source of inspiration for a sculptural work by Alexander Polzin, which was unveiled in 2013 at the Käte Hamburger Kolleg in the presence of the Indian Consul General, now at the Durkheim Research Centre.

The naming of an Ambedkar Fellowship at the Émile Durkheim Research Centre honours an important scientist and activist who sought to break the shackles of caste society in order to work for a fairer world as a lawyer, jurist and economist. By establishing the Ambedkar Fellowship, we hope to benefit from the fruitfulness of research perspectives developed in India in particular, which are associated with the names Upendra Baxi, Homi Bhabha and Dipesh Chakrabarty.

Chie Nakane (1926-2021) - Fellowship

Much like America became the sociological paradigm for the New World—from Tocqueville to Weber and Baudrillard—and India the pilgrimage site for 'Legal Pluralism' and 'Hybridity,' Japan has gained paramount significance for understanding the relationship between tradition and modernity. This is reflected in the works of Ruth Benedict, Robert N. Bellah, and Chie Nakane. Nakane succeeded in identifying the particular features of Japanese society, such as the ie (household) system, while at the same time making a significant contribution to the foundations of anthropology and sociology with her research into universally vertical societal structures. She did not so much theorize feminist concerns as practice them: she became the first female assistant and eventually a professor at the University of Tokyo. Her research in India and Japan was highly regarded by academic communities as well as the broader public. She was awarded the Order of Culture and the Medal of Honour with Purple Ribbon. After her passing at the age of 94, there was talk of a condolence letter from the Emperor, but her family declined it, in line with the much-praised modesty of Chie Nakane.

Today, it seems she is not well known in Japan anymore, as my friend Masahiro Noguchi from Tokyo writes to me. The naming of a fellowship in her honor pays tribute to a great scholar who stood for the ideals of objectivity and clarity of thought—something anyone who has delved into her writings will have absorbed. With her focus on topics like love, kinship, and family, she also seems to me to be closely aligned with the tradition of Durkheimian sociology and the Année sociologique, which, incidentally, contains numerous reviews of society and law in Japan.